03.02.2019

03.02.2019Some of your favorite bacteria are domesticated

Just as in agriculture, domestication has usually been to the benefit of our taste buds.

There is so much potential in microbiology and so many bacteria we could come to terms with. Yet, so little time to wait for nature.

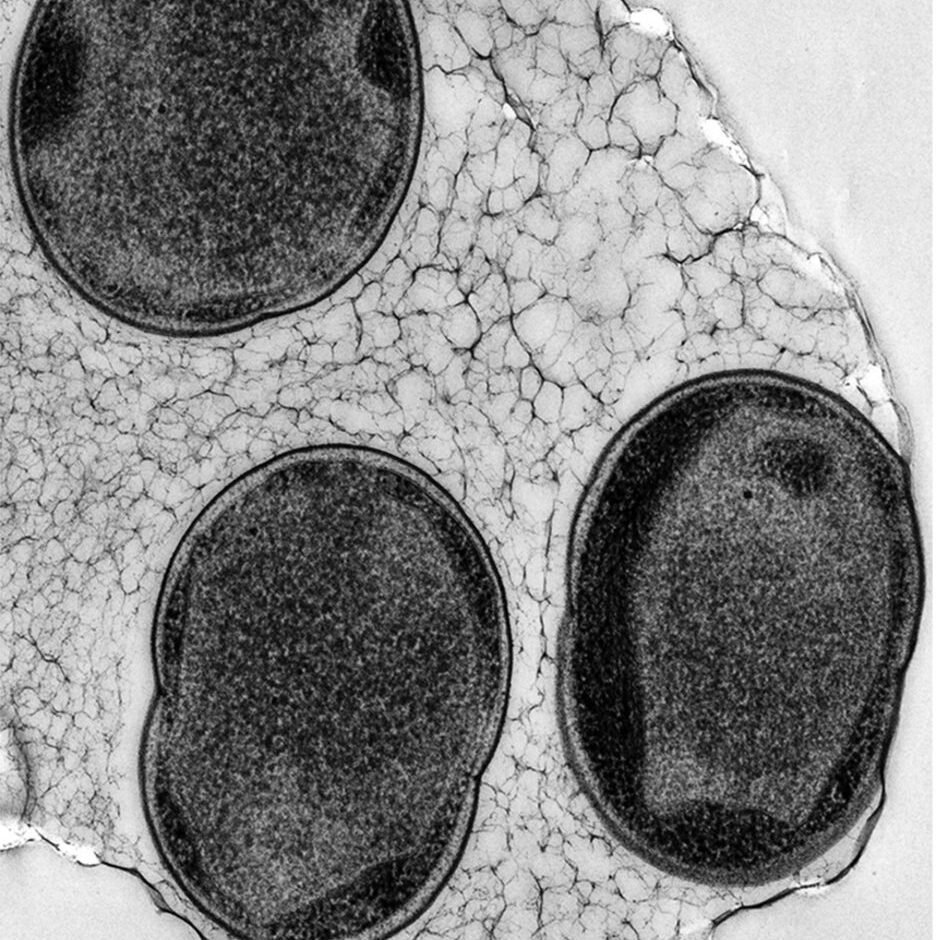

Transmission electron micrograph of Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum showing the chain of magnetosomes.

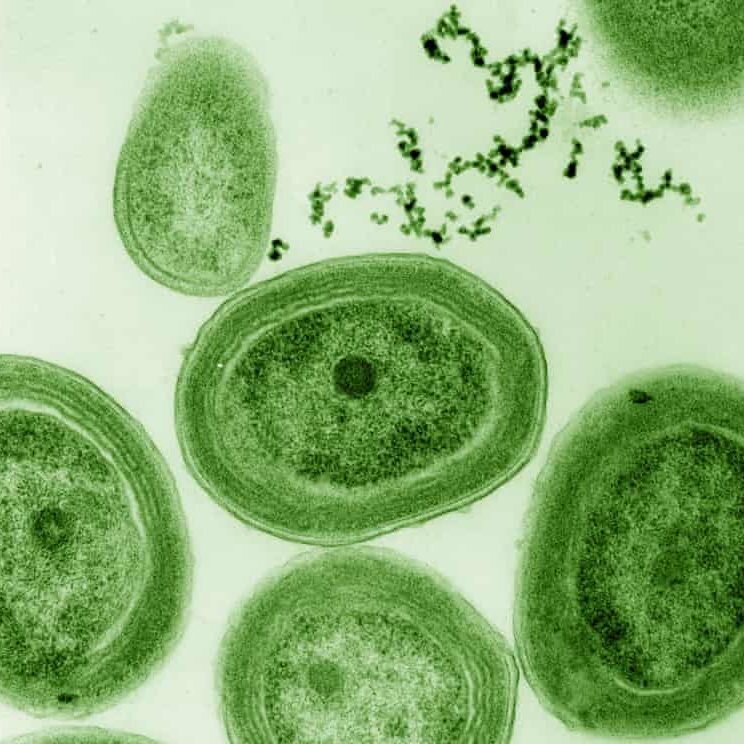

Transmission electron micrograph of Scalindua.

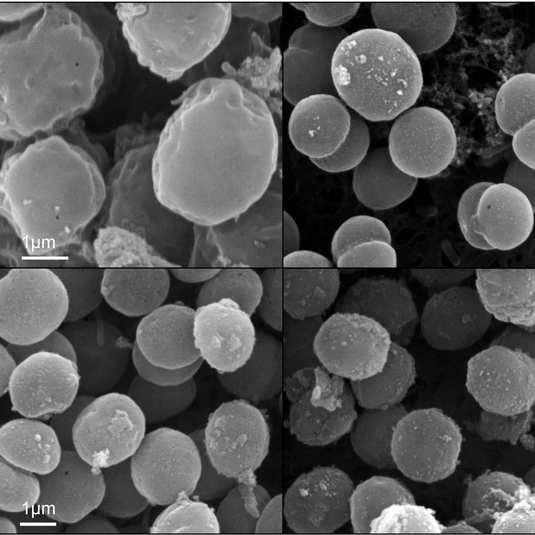

Scanning electron micrograph of four Microcystis aeruginosa strains.

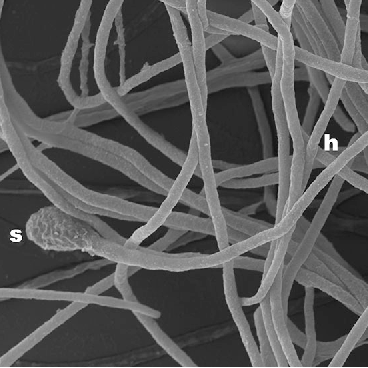

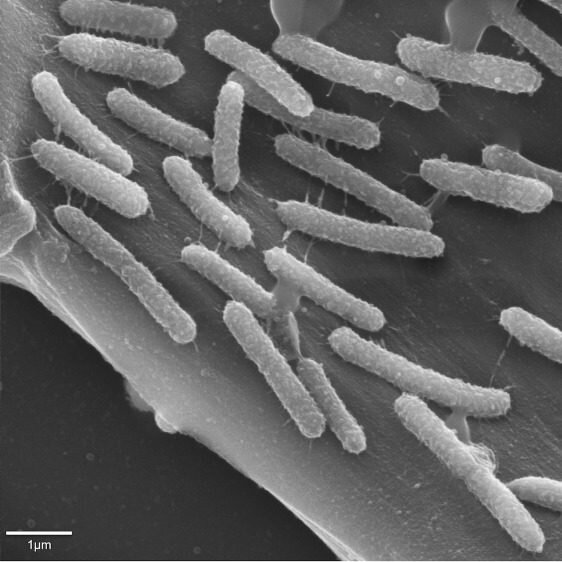

Scanning electron micrograph of a Frankia strain showing two morphological structures, hyphae (h) and sporangia (s).

First is Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum, an example of a magnetotactic bacteria that lives in freshwater and mineralizes metal so it can navigate the Earth’s magnetic field.

Second is Scalindua, an example of an Anammox bacteria. They are species that can make hydrazine from nitrogen rich environments (literally rocket fuel from urine).

Third is Microcystis aeruginosa, with a cool airbag mechanism to control their position in the water column.

Finally, fourth is Frankia bacteria, which fixes nitrogen for a shockingly broad range of plants. Bacteria like them protect plants without the need to add pesticides, herbicides, or synthetic fertilizer.

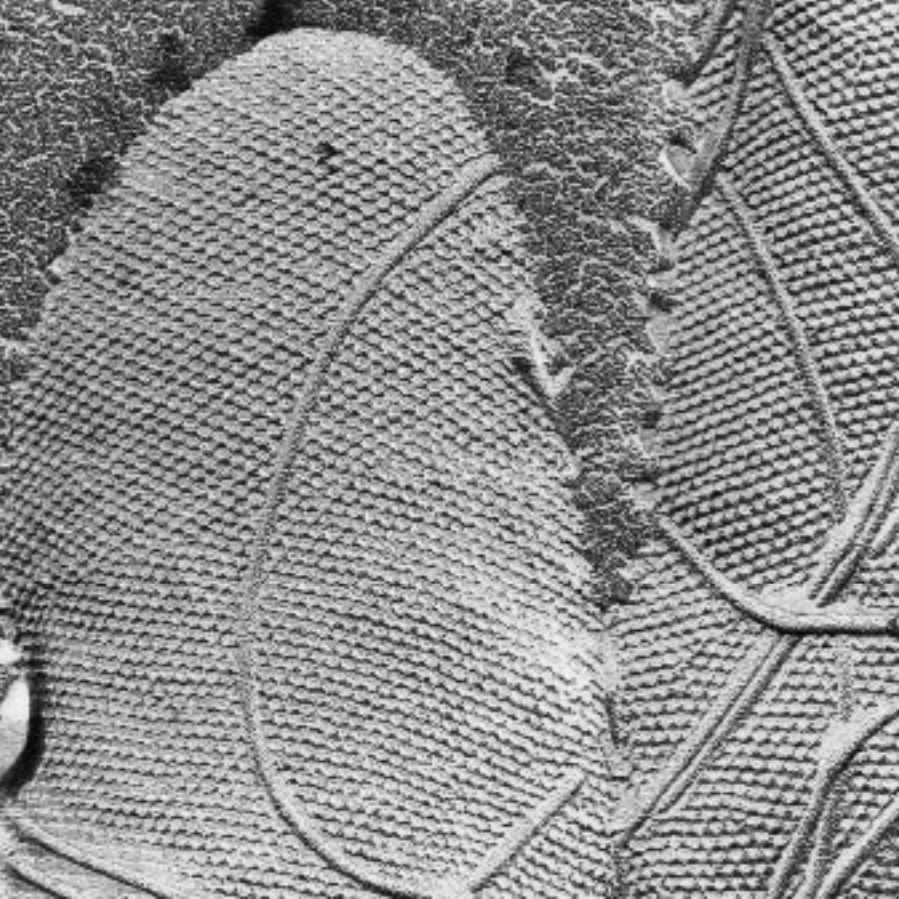

Electron micrographs of S-layer lattices on the surface of Thermoanaerobacter thermohydrosulfuricus.

Photograph: Luke Thompson from Chisholm Lab and Nikki Watson from Whitehead, MIT.

Scanning electron micrograph of Clostridium clariflavum.

First is Thermoanaerobacter thermohydrosulfuricus, an example of a heat loving bacteria that makes an S-layer, an amazing mesh nanomaterial that could be repurposed to capture pollutants in waters.

Second is Prochlorococcus, a cyanobacteria species. Such bacteria are responsible for at least half of our atmospheric oxygen.

Finally, third is Clostridium clariflavum, closely related to Clostridium thermocellum, representing the bacteria that break down celluloses found in grasses and rough biomasses. Find them deep inside your compost pile!

03.02.2019

03.02.2019Just as in agriculture, domestication has usually been to the benefit of our taste buds.

03.01.2019

03.01.2019Bioengineers have worked for thousands of years without the title, and there is no better proof of the success of that model than domestication.

02.15.2019

02.15.2019There is no such thing as a successful single organism ecosystem. Diversity is how we survive.