03.02.2019

03.02.2019Some of your favorite bacteria are domesticated

Just as in agriculture, domestication has usually been to the benefit of our taste buds.

Bioengineers have worked for thousands of years without being recognized as engineers, and there is no better proof of the success of that model than domestication. Lest we think of ourselves as exceptional, if you look around nature you cannot help but find organisms directly modifying each other’s behavior. When we catch organisms engaging in this behavior, we call it symbiosis. When ancient humans did it, we think of it as domestication. As we do it with modern tools, we call it genetic modification.

Ants and termites farm fungus, other ants farm aphids. Their patents must have expired by now!

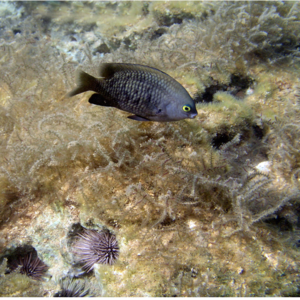

Damselfish farm a fungus we ourselves would probably prefer not to have around. They actively weed other fungi species and spit the chunks away at the edges of their gardens. They defend their patches aggressively; as a result their fungus is usually only found near them.

Monkeys in Japan have been spotted riding deer by offering them food (they might be getting up to other… shenanigans… with them, too).

Termites farming

Ants farming aphids

Damselfish farming fungus

A monkey riding a deer

Another example of how our engineering chops have been elided over: all of these plants are the same species called Brassica oleracea, or wild cabbage. Scroll through the images above to see what traits were enhanced in each plant.

All of these plants are the same species called Brassica Oleracea

Kale was selected for leaves

Broccoli was selected for flower buds and stems

Cauliflower was selected for flower buds

Cabbage was selected for terminal leaf buds

Brussels Sprouts for lateral leaf buds

Kohlrabi was selected for the stem

Romanesco is a broccoli hybrid

Gai Lan

Broccolini

I am bothered by two things: one, that all this massive effort in recruitment, selection, breeding, and refinement is taken for granted; and two, that in light of that we seem to be willing to stand pat for microbes! I comfort myself that it is the highest form of flattery, for an engineer, for people to take your work for granted, to be able to overlook the care and skill that went into a project. For them to immediately begin complaining about its battery life is for them to back-handedly admit that they cannot live without it.

In fact, we’re so proud of our ability to manipulate certain sets of recipes in other creatures that we brag about it to our children. Barnyard animals are a special set of genetically modified organisms we dominated so long ago that we’ve practically forgotten they didn’t always populate petting zoos.

Humans practically have been domesticating organisms since before recorded memory. Why do a job when you can just pay room and board for someone else to do it? Over hundreds and hundreds of years we have recognized the innate skills of our planetary cohabitants and then made them offers they couldn’t refuse.

Sometimes we were so successful in our subversion that it is hard to recognize our work, as in the engineering of corn from teosinte beginning eight thousand years ago. The strawberry entered our gardens seven hundred years ago. Cows probably joined our herd ten thousand years ago. We think dogs started heeling twenty thousand years ago.

The engineering of corn began eight thousand years ago.

Strawberries entered our gardens seven hundred years ago.

Cows joined our herd ten thousand years ago.

Dogs started heeling twenty thousand years ago.

03.02.2019

03.02.2019Just as in agriculture, domestication has usually been to the benefit of our taste buds.

02.16.2019

02.16.2019There is so much potential in microbiology, so many bacteria we could come to terms with, and not enough time to wait.

02.15.2019

02.15.2019There is no such thing as a successful single organism ecosystem. Diversity is how we survive.